The headliner did indeed finally arrive on Wednesday, August 3, after four interminable days of coming attractions - I mean, contractions.

Hell Week:

Last Saturday, Patty began feeling some minor cramping that morning, followed by some "show," a sure sign that her cervix was beginning to soften up for dilation. Things quieted down after breakfast and we spent a very nice day hitting the sidewalk sales going on throughout Andersonville. Then we stopped by our friends' condo for a birthday celebration, and as we were leaving, the cramping returned.

Then by 11:30, the cramping had turned into the first real contraction, and then about 15 minutes later, another one. Early labor was on.

For four nights in a row.

Saturday, Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday the contractions would begin around the same time, and last through the night - keeping us awake and dutifully tracking the intervals between, while we worked through the coping mechanisms learned in childbirth class. Then, just as regularly as they started, they'd slow and then stop just as the sun came up. During this time we became almost nocturnal, except we didn't sleep that much during the day either.

A brief break in the painful monotony came when we decided to go into triage at Prentice Women's Hospital after a tough Sunday night, when the intervals began closing to five minutes. They of course slowed as soon as we got into the cab, and once at the hospital we were told there was just a fingertip of dilation. They gave Patty a routine monitoring for fetal vitals, and sent us home.

We weren't sure what to do with ourselves, besides try to nap, so we did some of that and distracted ourselves in other ways. Monday night was no different, with even stronger contractions, and this time we knew we'd need to wait until it was flat out unbearable before going back to the hospital.

Tuesday was a great day once the contractions subsided. We had a yummy breakfast, took a long walk with Jack, then spent the afternoon at Hamlin Park pool, Patty walking back in forth in the cool water on a beautiful sunny day.

Once home, I began prepping for a long night by cooking all the veggies in the fridge to keep them from spoiling once we had to finally go into the hospital: a roasted beet salad w/ feta, egg salad w/ green onions, and a marinara.

"We need to go"

Arriving as timely as an Italian commuter train, the first contraction of the night hit at 11:30 and the next one less than 8 minutes later. I began getting our things ready. From midnight to 0300 we averaged 9 to 10 contractions per hour, and if they got any more intense...

At 0315, Patty was in the dining room and geared up for an approaching contraction. Bent over the buffet hutch, breathing and "ahhhhh"-ing she suddenly let out a yelp and burst into tears. This was it, the contraction that put it over the edge. Cab called. Jack watered. Lights out.

As the cabby was loading our gear into the trunk and Patty getting in the back seat, I calmly told him that this was not an emergency, we were hours, maybe even a day, from delivery, and that a baby would not be born in his car. He shook his head understandingly, then proceeded to drive us to Prentice down Lake Shore Drive at over 70mph, carving a line through the Oak Street chicane that Fabian Cancellara would admire.

"You're admitted!"

Once in triage we found out Patty was 3cm dilated. Normally, that wouldn't be enough to warrant admission, but the contractions were 5 minutes apart and closing, and we'd not slept because of them for four nights. Momma was running high blood pressure however, so the RN asked if we were planning on pain meds; we'd need blood work done to rule out pre-eclampsia, which could impact an epidural. We were definitely reconsidering our desire to go drug-free, so it was better to order the blood work now, in case she decided to grab my bottom lip and pull it over my head.

Around 0600 we found we ourselves in labor & delivery and things were really moving. The next cervical check showed a gain to 6cm in less than 90 minutes (typically, 1cm/hour is the benchmark). They broke Patty's bag, and then our OB showed up, at the end of his night shift to see how things were going. Patty was pretty sure at that point that she wanted an epidural, and after some discussion, we ordered it. It was right then active labor hit like an atom bomb.

As the contractions seemingly had no definable end or beginning, even coming on top of the last, the lab was delayed in getting the results of the blood work. Patty and I stood, arms interlocked, rocking back and forth there in the room. At first we were alone (she burst into tears when seeing the blood-tinged fluid accumulating on the floor between her legs), then amid doctors and nurses who made welcome lighthearted jokes about 7th grade slow dances and that, "it's not the cleanest of medical practices." They told us we were really working well together, using our coping skills expertly. Breathing and "ahhhhhhhhhhhh!"-ing our way through the worst pain Patty had ever experienced in her life, with me sternly reminding her to stay in control, and not give it up to the agony.

Relief

After what seemed like hours (in reality about 75 minutes) the epidural was approved and I was told I'd need to step out when it was administered. Anesthesia soon showed around 7:30, and I left for some cafeteria breakfast. Upon returning, it was as if I'd walked into the wrong room. Patty was lying peacefully on her side, the motor of the IV drip humming along soothingly. No one else was there.

The next cervical check at 0800 showed another gain, out to 8cm; as well as 100% effaced and at 0 station. We were ecstatic. Dr. Chen, the OB who would be delivering Baby Mo then said, "I'll be back in about 90 minutes. You should be feeling strong pressure on your rectum, and we'll be ready to push!"

I happily reported via text to family members that we could expect a new baby by 11am.

Stalled

The next cervical check indicated no change, so a small dose of pitocin was added. It was hard to interpret the monitor's contraction readout but it did seem as though the action had begun to slow. I then had lunch, watched a movie, but anxiety had begun to creep in. It was evident in Patty as well. Two more cervical exams revealed no change, and each time the pitocin dosage was slightly increased.

I warily noticed long intervals in between gently sloping contractions and Baby Mo's heart rate rising to the upper limit of normal, high 150s. Patty was also running a 101 fever, indicative of a possible uterine infection. The pitocin wasn't working like we wanted it to, and Patty and I were trying to work through a sudoku puzzle to calm ourselves when Dr. Chen walked in around 1420. Cervix was still at 8cm.

She told us that she was going to do a Cesarean-section procedure and would be back in a couple hours. If Patty made progress in that time, and felt the need to push suddenly, a midwife was on the floor who could deliver Baby Mo. If there was no progress, "we'd need to consider other options."

There was no delusion that "other options" was only one option.

I tried to not show my growing fear. Barely anyone wants a c-section and this was the dreaded end after 4 weeks of child birth classes and long discussions about delivery: cutting the chord, baby going straight to momma, maybe even standing birth. C-sections are far more common in the United States - nearly 40% of total births - largely because of the more medical/surgical nature of obstetrics in this country.

Dr. Chen returned by 1600 and when Patty told her that she felt some pressure, all of our spirits jumped. It could be the progress we were hoping for. A check of her cervix revealed, however, that we'd be going into surgery.

Not that we had any other choice. As I sat there, unable to speak while doctors and nurses came in to prep Patty for surgery and sign the necessary waivers, I couldn't find any regret for our course of action up to now. Four days of sleepless nights and painful contractions, breaking the bag, the necessity of the epidural...I wouldn't have changed any of it. If a Cesarean resulted from the chain reaction of interventions, then I could live with that.

It still didn't keep me from being scared shitless.

"I need you to stay calm for me"

I had 20 minutes alone in the labor & delivery room after they wheeled Patty away for surgery. I was to put on the scrubs they left for me, and wait for the RN to come and take me to the operating room for delivery. I sat there shaking and trying not to think about all the things that could go wrong with a very routine surgery on a women with a 101 fever and elevated blood pressure - not that I knew anything at all about surgery, except that when I was a little kid even M*A*S*H episodes used to scare me.

The RN was back to get me more quickly than I expected, and walking out with her to the OR was an out of body experience. I was watching myself as though I were a different person.

It was hyper-real. The operating room was as bright as a high school detention class. Not dark, like in M*A*S*H episodes, or in the movies. I didn't have to wash my hands, or go through an air lock. The voices and mannerisms of all the doctors and RNs oozed confidence and professional detachment while my ears were attuned to any reveal of something going wrong, through a shaky or hesitant word, or sharply issued order. I only heard deliberate footsteps, regimental dialog, and a few casual comments mixed in with the beeps and whirs of the surgical apparatuses all over the room.

A large green surgical sheet was up between us and the action and I could only see Patty from the chest up. Her arms were spread crucifix-like from her sides and she looked up at me - noticing my hurried breathing and darting eyes above my face mask - and with relaxed panic, said,

"I need you to be calm for me."

Catharsis

Those words were like an order from a general to a private as he was about to go around a wall into a hail of gunfire. I owed it to her to place my trust in the hospital, the doctors, in our own decisions that brought us to this moment. There was no going back, nothing I could do but face the situation for what it was. We were moments away from putting the last nine months behind us forever.

I stroked her cheek and just nodded, my eyes stealing in response. As I looked at the floor, deliberately slowing my breathing with deep draws from my diaphragm, I heard Dr. Chen say, jokingly:

"I think I'm more concerned about the dad than the patient!"

And then,

"Dad, you can stand up now!"

My knees straightened, my back became upright, and I watched the green sheet between me and the source of all the unseen activity move downward followed by its top edge and then the open space of the room...

I was looking at Baby Mo at the moment she was being pulled from the womb, 1656 hours on August the 3rd, 2011, covered in murky fluid and blood, unfolding from her fetal position, and held up for me to see by Dr. Chen, whose eyes were smiling brightly from behind her mask. I didn't consciously try to count 10 finger and toes, or two eyes, or see the quivering mouth, but when I heard her new, untested voice gurgling and then gaining strength into an angry shriek, I knew Baby Mo was with us to stay.

I didn't realize I was weeping until I felt the gush of tears down my face.

When I looked down at Patty she was weeping too, having watched my reaction, and then Baby Mo was whisked away to the side room for all the measurements to make sure she was, in fact, a live human baby, despite the confirming evidence of her continued bellowing and shrieking at the indignation at having been ripped naked from the only existence she'd ever known.

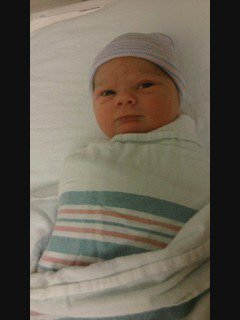

Vivian

The relief continued to flow, morphing to joy, as I heard the OR staff laughing and joking approvingly at the healthy sounds of displeasure. The pediatrician was then waving me to come around and join him in the room for a first picture. Baby Mo was definitely a live human baby, all eight pounds, 4 ounces, and 20 inches of her, and named Vivian Rose Morrissey.

Patty was lying just as helpless in the next room, waiting for more than 15 minutes to finally touch the skin of her new baby. I was soon able to place Vivian in her arms before they moved them from the OR into recovery.